Persona

YouTube viewing

I think for a long time, the phrase “art cinema” was synonymous with Ingmar Bergman: black and white; really deep thoughts about Life, The Universe and Everything; playing chess with Death and other abstract visuals, etc. And to Bergman’s credit, he became popular enough that such imagery became so cliche. But does that mean people love his films the way they love those of Kubrick or Scorsese?

There are a bunch of YouTube videos in which critics and filmmakers and scholars talk at length about why Bergman is so great and what his films are “really” all about, but if I’m coming at him from the perspective of just another film fan, albeit one with a little more knowledge of film history than some, I shouldn’t need any of that for me to appreciate his work; indeed, I’m trying hard to avoid those videos while writing this post about Persona because I want to be as unbiased in my opinions as possible.

Some might say knowing Bergman and his worldview is necessary to grok his films—but did the average moviegoer have that information when he made his movies during the sixties, pre-Internet? If Bergman was the capital-A Ar-TEEst he was proclaimed to be, I imagine he’d have wanted his work to speak for itself. So let’s give it a shot.

Thursday, April 30, 2020

Friday, April 24, 2020

Diabolique (1955)

Diabolique (1955) (AKA Les Diaboliques)

YouTube viewing

In 1940, Henri-Georges Clouzot was in a desperate state. The screenwriter had spent five years in a sanatorium during the 30s, recovering from tuberculosis, and while he had used the time to further study his craft, his scripts were selling poorly and he was running out of money. Meanwhile, World War 2 had broken out. When an offer came his way to work for a German-based film production company, HGC had no choice but to take it.

It led to him becoming a director, but after the war, he and other filmmakers were tried in court as German collaborators. He was banned from making films for life, but that sentence was reduced to only two years thanks to a bunch of artists rallying to his cause, including Jean Cocteau, Rene Clair and Jean-Paul Sartre.

Thanks to their efforts in reducing his exile, HGC went on to become one of the finest filmmakers in the long and proud history of French cinema, and one of his greatest hits is today’s subject, Diabolique, an entertaining thriller he co-adapted from a book and made with his wife.

Brazilian actress Vera Gibson-Amado had divorced French actor Leo Lapara when she met HGC in the late 40s. Lapara had roles in earlier HGC films and she worked as a continuity assistant. Long story short, Vera and HGC fell in love, got married and she became Vera Clouzot.

As a film actress, she would only make three films before her death from a heart attack in 1960, but they were all for her husband and the production company named for her, Vera Films. Diabolique was one. If it feels like a Hitchcock film to you, well, the Master did express an interest in making it, but HGC beat him to the punch.

In the movie, the wife and mistress of the same man conspire to kill him, but after they do the deed, strange things occur that lead them to believe he’s not as dead as they thought. Vera plays the wife, future Oscar winner Simone Signoret plays the mistress. Their characters both work for male lead Paul Meurisse, the man in both their lives, in the same boarding school, so they’re all closely connected even outside their infidelities.

As you might expect, the mounting evidence that something about the murder didn’t go right hinders the women’s partnership, and while their triangle is an open secret amongst their co-workers (and even the kids in the school), Meurisse’s sudden disappearance raises some uncomfortable questions the women have to deal with. The truth revealed at the end definitely surprised me, though I had to think further to remember the clues as to its plausibility.

YouTube viewing

In 1940, Henri-Georges Clouzot was in a desperate state. The screenwriter had spent five years in a sanatorium during the 30s, recovering from tuberculosis, and while he had used the time to further study his craft, his scripts were selling poorly and he was running out of money. Meanwhile, World War 2 had broken out. When an offer came his way to work for a German-based film production company, HGC had no choice but to take it.

It led to him becoming a director, but after the war, he and other filmmakers were tried in court as German collaborators. He was banned from making films for life, but that sentence was reduced to only two years thanks to a bunch of artists rallying to his cause, including Jean Cocteau, Rene Clair and Jean-Paul Sartre.

Thanks to their efforts in reducing his exile, HGC went on to become one of the finest filmmakers in the long and proud history of French cinema, and one of his greatest hits is today’s subject, Diabolique, an entertaining thriller he co-adapted from a book and made with his wife.

Brazilian actress Vera Gibson-Amado had divorced French actor Leo Lapara when she met HGC in the late 40s. Lapara had roles in earlier HGC films and she worked as a continuity assistant. Long story short, Vera and HGC fell in love, got married and she became Vera Clouzot.

As a film actress, she would only make three films before her death from a heart attack in 1960, but they were all for her husband and the production company named for her, Vera Films. Diabolique was one. If it feels like a Hitchcock film to you, well, the Master did express an interest in making it, but HGC beat him to the punch.

In the movie, the wife and mistress of the same man conspire to kill him, but after they do the deed, strange things occur that lead them to believe he’s not as dead as they thought. Vera plays the wife, future Oscar winner Simone Signoret plays the mistress. Their characters both work for male lead Paul Meurisse, the man in both their lives, in the same boarding school, so they’re all closely connected even outside their infidelities.

As you might expect, the mounting evidence that something about the murder didn’t go right hinders the women’s partnership, and while their triangle is an open secret amongst their co-workers (and even the kids in the school), Meurisse’s sudden disappearance raises some uncomfortable questions the women have to deal with. The truth revealed at the end definitely surprised me, though I had to think further to remember the clues as to its plausibility.

Perhaps you remember Sharon Stone’s remake in 1996. If not, you didn’t miss much; it bombed big time.

Wednesday, April 22, 2020

Tokyo Story

Tokyo Story

YouTube viewing

It’s time once again for us to eat our cinematic vegetables! I’ve gotten kinda flabby around the middle gorging on Hollywood films, so I’m gonna change my diet for awhile and indulge in a few foreign movies, the kind that are supposed to be “good for you.”

Don’t get me wrong; I’m only being slightly serious about this. It’s one of the oldest debates on this blog: just because some big-shot critic says a certain movie is great, does that mean you have to like it too? Especially if it comes across as “boring”? (Please note the quotation marks around that word.) I still haven’t found the answer to that question; I doubt I ever will—but I do want to mix things up around here and look at some foreign films.

Japanese filmmaker Yasujiro Ozu is one whom I’ve heard a lot about but whose work I had never seen before. Omigod, do the critics fall all over themselves praising this guy: his films often make the “all-time best of” lists, Criterion has his films in its collection, they discuss him in film school, the works—so he must be worth watching, right? Well, I was very lucky to have found one of his biggest hits online to watch: the film Tokyo Story. I’m pleased to say I thought it was good, though it took quite awhile for me to appreciate.

YouTube viewing

It’s time once again for us to eat our cinematic vegetables! I’ve gotten kinda flabby around the middle gorging on Hollywood films, so I’m gonna change my diet for awhile and indulge in a few foreign movies, the kind that are supposed to be “good for you.”

Don’t get me wrong; I’m only being slightly serious about this. It’s one of the oldest debates on this blog: just because some big-shot critic says a certain movie is great, does that mean you have to like it too? Especially if it comes across as “boring”? (Please note the quotation marks around that word.) I still haven’t found the answer to that question; I doubt I ever will—but I do want to mix things up around here and look at some foreign films.

Japanese filmmaker Yasujiro Ozu is one whom I’ve heard a lot about but whose work I had never seen before. Omigod, do the critics fall all over themselves praising this guy: his films often make the “all-time best of” lists, Criterion has his films in its collection, they discuss him in film school, the works—so he must be worth watching, right? Well, I was very lucky to have found one of his biggest hits online to watch: the film Tokyo Story. I’m pleased to say I thought it was good, though it took quite awhile for me to appreciate.

Monday, April 20, 2020

The Emperor Jones

The Emperor Jones

YouTube viewing

How awesome was Paul Robeson? The son of a former slave, he graduated high school and college as class valedictorian. He played in the NFL while studying law. He was successful on the foreign and domestic stage. He was one of the top recording artists of the 20th century. He was a civil rights activist and supported progressive political causes in other countries. He wasn’t a saint—he cheated on his wife multiple times, for instance—but he was a proud black man who saw and did it all during a time when institutional racism held back many black people in America. Oh, and he made movies too.

Among the many, many awards and tributes he received, both in life and death, include the naming of a Manhattan apartment building after him. Robeson lived in what is now The Paul Robeson Residence in uptown Washington Heights from 1939-41, and was one of the first black tenants. Count Basie and Joe Louis also lived there. It’s both a civic and national landmark—and the street on which it resides, Edgecombe Avenue, is co-named “Paul Robeson Boulevard.”

Of course he has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. A Criterion box set of his films is available. James Earl Jones starred as Robeson in a one-man Broadway play which was turned into a TV movie. 12 Years a Slave director Steve McQueen had plans for a biopic, though that was over five years ago.

YouTube viewing

How awesome was Paul Robeson? The son of a former slave, he graduated high school and college as class valedictorian. He played in the NFL while studying law. He was successful on the foreign and domestic stage. He was one of the top recording artists of the 20th century. He was a civil rights activist and supported progressive political causes in other countries. He wasn’t a saint—he cheated on his wife multiple times, for instance—but he was a proud black man who saw and did it all during a time when institutional racism held back many black people in America. Oh, and he made movies too.

Among the many, many awards and tributes he received, both in life and death, include the naming of a Manhattan apartment building after him. Robeson lived in what is now The Paul Robeson Residence in uptown Washington Heights from 1939-41, and was one of the first black tenants. Count Basie and Joe Louis also lived there. It’s both a civic and national landmark—and the street on which it resides, Edgecombe Avenue, is co-named “Paul Robeson Boulevard.”

Of course he has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. A Criterion box set of his films is available. James Earl Jones starred as Robeson in a one-man Broadway play which was turned into a TV movie. 12 Years a Slave director Steve McQueen had plans for a biopic, though that was over five years ago.

Labels:

classic cinema,

drama,

live theater,

movie stars,

race,

writing

Sunday, April 19, 2020

Double Harness

Double Harness

TCM viewing

Often with old Hollywood movies, one gets a glimpse into the morality of the times they were made in, which were dramatically different from today. For one who never lived in those times, who only knows of them secondhand, it can drive one crazy to see—and by “one,” of course, I’m talking about Yours Truly, but it sounds fancier and more highfalutin’ if I phrase it that way, don’t you think?

I have trouble imagining real people acting the way they do in Double Harness, partly because it’s about rich white people who apparently have nothing better to do than play head games with each other over love and marriage, but also because the rules of the game, the implied moral code that defines their privileged and rarefied world, has little bearing on the 21st century world from which I’m observing. Most of the time, I can play along, accept this sort of thing at face value and say okay, I get it, this is how people acted back then and I just have to accept it. Sometimes, I can’t.

As I write this, it occurs to me that tone helps. If this was an Ernst Lubitsch comedy, it would’ve gone down much, much easier—but the women and men in this movie are so earnest about how they should behave towards each other, even when they do things they probably shouldn’t, it makes me wanna say “Get over yourselves!” to the lot of them. Are these the kinds of things worth occupying your time?

Ann Harding is a single high-society dame whose little sister is getting married and, perhaps hearing her own biological clock ticking, starts getting Ideas about what it takes to grab a man. She hypothesizes love is unnecessary in a marriage because Reasons. Platonic pal William Powell is a playboy heir who likes to run around. She launches a scheme to trap him into marriage and make an honest man out of him. It works, but complications, as they often do, ensue.

At the start, Harding is convinced she doesn’t have much to offer a potential husband, though it’s not like she’s down and out, especially given that Harness acknowledges the Great Depression as a fact of everyday life, more than once. She’s not standing on any bread lines. She can afford to go to the theater in the evenings in fancy dress, and she’s easy on the eyes. But I guess none of that is enough.

Her scheme depends on the notion that it’s improper for her to be alone with Powell in his pad, given his reputation—because it’s not like her family and acquaintances know him and her to be good friends who treat each other well, or more importantly, like she was a grown-ass woman and who she chooses to spend time alone with is her own damn business.

But her father catches the two of them talking like the consenting adults they are and concludes Powell must be putting the make on her, and she must be letting him (a much worse crime, of course)—therefore Powell must do “the honorable thing” and marry her, something he’s not eager to do, though not necessarily because of her. No one questions any of this because these are the rules of the game. Harding counts on her father’s reaction because she’s playing a game of her own, but the whole thing, the father’s attitude and Harding’s scheme alike, does not sound like normal human behavior.

Powell warns Harding that he’ll make a lousy husband, and sure enough, he chases around an old flame who also got recently married but still carries a torch for Powell. Meanwhile, little sister spends so much of her husband’s money she gets in debt. And how sure is Harding about this whole marriage-without-love plan anyway? This stuff was more interesting, but getting there was the hard part, because none of this felt like it mattered.

TCM played Harness as part of a TCM Film Festival “greatest hits” weekend, in lieu of the canceled actual fest. Karen singled Harness out as worth watching, so I gave it a try. It wasn’t terrible—Powell is always worth watching—I just felt uncomfortable with the triviality of the plot.

TCM viewing

Often with old Hollywood movies, one gets a glimpse into the morality of the times they were made in, which were dramatically different from today. For one who never lived in those times, who only knows of them secondhand, it can drive one crazy to see—and by “one,” of course, I’m talking about Yours Truly, but it sounds fancier and more highfalutin’ if I phrase it that way, don’t you think?

I have trouble imagining real people acting the way they do in Double Harness, partly because it’s about rich white people who apparently have nothing better to do than play head games with each other over love and marriage, but also because the rules of the game, the implied moral code that defines their privileged and rarefied world, has little bearing on the 21st century world from which I’m observing. Most of the time, I can play along, accept this sort of thing at face value and say okay, I get it, this is how people acted back then and I just have to accept it. Sometimes, I can’t.

As I write this, it occurs to me that tone helps. If this was an Ernst Lubitsch comedy, it would’ve gone down much, much easier—but the women and men in this movie are so earnest about how they should behave towards each other, even when they do things they probably shouldn’t, it makes me wanna say “Get over yourselves!” to the lot of them. Are these the kinds of things worth occupying your time?

Ann Harding is a single high-society dame whose little sister is getting married and, perhaps hearing her own biological clock ticking, starts getting Ideas about what it takes to grab a man. She hypothesizes love is unnecessary in a marriage because Reasons. Platonic pal William Powell is a playboy heir who likes to run around. She launches a scheme to trap him into marriage and make an honest man out of him. It works, but complications, as they often do, ensue.

At the start, Harding is convinced she doesn’t have much to offer a potential husband, though it’s not like she’s down and out, especially given that Harness acknowledges the Great Depression as a fact of everyday life, more than once. She’s not standing on any bread lines. She can afford to go to the theater in the evenings in fancy dress, and she’s easy on the eyes. But I guess none of that is enough.

Her scheme depends on the notion that it’s improper for her to be alone with Powell in his pad, given his reputation—because it’s not like her family and acquaintances know him and her to be good friends who treat each other well, or more importantly, like she was a grown-ass woman and who she chooses to spend time alone with is her own damn business.

But her father catches the two of them talking like the consenting adults they are and concludes Powell must be putting the make on her, and she must be letting him (a much worse crime, of course)—therefore Powell must do “the honorable thing” and marry her, something he’s not eager to do, though not necessarily because of her. No one questions any of this because these are the rules of the game. Harding counts on her father’s reaction because she’s playing a game of her own, but the whole thing, the father’s attitude and Harding’s scheme alike, does not sound like normal human behavior.

Powell warns Harding that he’ll make a lousy husband, and sure enough, he chases around an old flame who also got recently married but still carries a torch for Powell. Meanwhile, little sister spends so much of her husband’s money she gets in debt. And how sure is Harding about this whole marriage-without-love plan anyway? This stuff was more interesting, but getting there was the hard part, because none of this felt like it mattered.

TCM played Harness as part of a TCM Film Festival “greatest hits” weekend, in lieu of the canceled actual fest. Karen singled Harness out as worth watching, so I gave it a try. It wasn’t terrible—Powell is always worth watching—I just felt uncomfortable with the triviality of the plot.

Thursday, April 16, 2020

Gulliver’s Travels (1939)

Gulliver’s Travels (1939)

YouTube viewing

In 1726, before the American Revolution, before the births of Thomas Jefferson, Charles Darwin and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Jonathan Swift published a novel with the humble title Travels Into Several Remote Nations of the World in Four Parts by Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and Then a Captain of Several Ships. And if you think that’s long, you should’ve seen what he wanted to call it!

Swift’s piece of speculative fiction was a brutal satire of British society and politics, but somewhere along the way, people only remembered the tiny people and the giants and reinterpreted it as kiddie lit, which I suppose is like reading Animal Farm, remembering only the talking animals, and turning it into a nursery rhyme. Anyway, by 1939, it was deemed safe for the younglings and thus was turned into an animated musical because amusing little kids was totally Swift’s true intent all along.

I had talked about Fleischer Studios here before—the animation studio responsible for Betty Boop, Popeye, and other early 20th-century cartoon characters. They first brought Superman to the big screen shortly after his creation. Their rotoscoping technique of animation would be duplicated at Disney and elsewhere for decades to come.

YouTube viewing

In 1726, before the American Revolution, before the births of Thomas Jefferson, Charles Darwin and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Jonathan Swift published a novel with the humble title Travels Into Several Remote Nations of the World in Four Parts by Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and Then a Captain of Several Ships. And if you think that’s long, you should’ve seen what he wanted to call it!

Swift’s piece of speculative fiction was a brutal satire of British society and politics, but somewhere along the way, people only remembered the tiny people and the giants and reinterpreted it as kiddie lit, which I suppose is like reading Animal Farm, remembering only the talking animals, and turning it into a nursery rhyme. Anyway, by 1939, it was deemed safe for the younglings and thus was turned into an animated musical because amusing little kids was totally Swift’s true intent all along.

I had talked about Fleischer Studios here before—the animation studio responsible for Betty Boop, Popeye, and other early 20th-century cartoon characters. They first brought Superman to the big screen shortly after his creation. Their rotoscoping technique of animation would be duplicated at Disney and elsewhere for decades to come.

Monday, April 13, 2020

Algiers

Algiers

YouTube viewing

In Jeanine Basinger’s book about the Old Hollywood approach to creating movie stardom, The Star Machine, she says that Charles Boyer “was every American moviegoer’s idea of Big-time French.” I imagine he came across as pretty exotic and cosmopolitan to audiences back then, like Maurice Chevalier and Jean Gabin. These days, when I think of French thespians, I tend to think of the ladies—Catherine Deneuve, Brigitte Bardot, Audrey Tatou, Juliette Binoche—before any fellas.

Even before the actors, though, I associate French cinema with the directors who came out of the New Wave era: Godard, Truffaut, etc. Call it a cultural shift, one where who makes a film became as important, if not more so, than who’s in it. The French were greatly responsible for that. Now that’s big-time.

I can’t say I know a great deal about Boyer beyond what I’ve read. MGM originally wanted him to do foreign-language versions of their English language hits, but once dubbing was used, duplicates became unnecessary. Hollywood still wanted Boyer, but he had to improve his English first (he could speak five other languages and made movies not only in France, but Germany too). He came back to Hollywood in 1934 and once it was determined the ladies in the audience responded to him, that’s when his stardom in America took off.

Algiers was the film that put him over the top. Set in the North African city in Algeria, it focuses on a French criminal who, after pulling off a major jewelry heist, set up shop in the seedy criminal quarter known as the Casbah and became a big-shot there for years. The cops could never touch him because he was so well-protected, but now they have a plan, which comes right as Boyer feels restless and is ready to leave the neighborhood he may rule like a king, but which has also become a prison to him.

The Casbah was in pretty bad shape even before this year. UNESCO declared it a “world heritage site” and efforts have been made to preserve it, despite the political upheavals of recent decades. This New York Times article goes into more detail. Plus, here are some first-hand accounts of the current state of the neighborhood.

It was hard to not look at Algiers through 21st-century eyes. I didn’t completely buy the cliche of glamor-girl Hedy Lamarr falling for bad-boy Boyer, though I did accept him falling for her. She represented the France he missed after being away for so long and believed he could recapture again—the movie hammers this point home pretty well. (I liked the line about how she reminded him of the subway.) I was reminded of Casablanca: foreigner in a foreign country he has learned to call home gets hung up over a girl who reminds him of the past but represents danger. Setting plays a vital role; as does local law and order.

Basinger discusses what made Boyer a star in his day:

A brief word about Lamarr. Much has been written about her prowess as a scientist and her contributions to inventions that still impact modern society. This was the first time I had seen her as an actress, and I can’t say I was bowled over by her. She wasn’t bad, but she wasn’t distinctive in the way a Garbo or a Dietrich were. She was gorgeous, but that was the extent of it. I probably need to see more of her films. If it weren’t for her, though, I couldn’t write this post for you to read on the Internet, so there’s that. Last year, Deadline announced that Gal Gadot would star in a biopic of Lamarr.

YouTube viewing

In Jeanine Basinger’s book about the Old Hollywood approach to creating movie stardom, The Star Machine, she says that Charles Boyer “was every American moviegoer’s idea of Big-time French.” I imagine he came across as pretty exotic and cosmopolitan to audiences back then, like Maurice Chevalier and Jean Gabin. These days, when I think of French thespians, I tend to think of the ladies—Catherine Deneuve, Brigitte Bardot, Audrey Tatou, Juliette Binoche—before any fellas.

Even before the actors, though, I associate French cinema with the directors who came out of the New Wave era: Godard, Truffaut, etc. Call it a cultural shift, one where who makes a film became as important, if not more so, than who’s in it. The French were greatly responsible for that. Now that’s big-time.

I can’t say I know a great deal about Boyer beyond what I’ve read. MGM originally wanted him to do foreign-language versions of their English language hits, but once dubbing was used, duplicates became unnecessary. Hollywood still wanted Boyer, but he had to improve his English first (he could speak five other languages and made movies not only in France, but Germany too). He came back to Hollywood in 1934 and once it was determined the ladies in the audience responded to him, that’s when his stardom in America took off.

Algiers was the film that put him over the top. Set in the North African city in Algeria, it focuses on a French criminal who, after pulling off a major jewelry heist, set up shop in the seedy criminal quarter known as the Casbah and became a big-shot there for years. The cops could never touch him because he was so well-protected, but now they have a plan, which comes right as Boyer feels restless and is ready to leave the neighborhood he may rule like a king, but which has also become a prison to him.

The Casbah was in pretty bad shape even before this year. UNESCO declared it a “world heritage site” and efforts have been made to preserve it, despite the political upheavals of recent decades. This New York Times article goes into more detail. Plus, here are some first-hand accounts of the current state of the neighborhood.

It was hard to not look at Algiers through 21st-century eyes. I didn’t completely buy the cliche of glamor-girl Hedy Lamarr falling for bad-boy Boyer, though I did accept him falling for her. She represented the France he missed after being away for so long and believed he could recapture again—the movie hammers this point home pretty well. (I liked the line about how she reminded him of the subway.) I was reminded of Casablanca: foreigner in a foreign country he has learned to call home gets hung up over a girl who reminds him of the past but represents danger. Setting plays a vital role; as does local law and order.

Basinger discusses what made Boyer a star in his day:

To American audiences, Charles Boyer seemed the perfect lover for many reasons, Algiers chief among them. But women also thought he was a gentleman.... he had that gentlemanly quality, that elegance, that sense that he was offering his arm to a lady. He was an exotic French lover Americanized, democratized, and because of that, he seemed to be perfect to play in support of female movie stars.Boyer seemed like a cliche to me only because his type had been imitated and parodied many times since Algiers. Sometimes it really is necessary to attempt to see an old movie the way audiences of its time saw it in order to appreciate it better. I haven’t mastered that ability yet.

|

| Sigrid Gurie (second-billed over Lamarr) plays this local chick totally hung up on Boyer for reasons I couldn’t exactly fathom. He, of course, takes her completely for granted. |

A brief word about Lamarr. Much has been written about her prowess as a scientist and her contributions to inventions that still impact modern society. This was the first time I had seen her as an actress, and I can’t say I was bowled over by her. She wasn’t bad, but she wasn’t distinctive in the way a Garbo or a Dietrich were. She was gorgeous, but that was the extent of it. I probably need to see more of her films. If it weren’t for her, though, I couldn’t write this post for you to read on the Internet, so there’s that. Last year, Deadline announced that Gal Gadot would star in a biopic of Lamarr.

Friday, April 10, 2020

Lady of Burlesque

Lady of Burlesque

YouTube viewing

Well, I certainly didn’t expect a murder mystery from a movie titled Lady of Burlesque! Maybe I should’ve looked at the poster first. This one was kinda hard to follow for three reasons: a huge cast, with most of them talking a mile a minute, and in a hipster lingo from almost a century ago. It was worth it, though, to see Barbara Stanwyck shaking her moneymaker!

The history of burlesque dancing is a long one, covering much of world history, cultural mores, fashion, etc. Here’s a Cliff Notes version written by modern burlesque dancer Dita von Teese. For this post, we need to focus on one dancer in particular.

Gypsy Rose Lee was exposed to showbiz early in life. To support the family, she performed in vaudeville, dancing with her older sister, June Havoc, as kids. When June eloped, GRL was able to continue solo as a striptease artist. The legend has it that she chose this path when she had a wardrobe malfunction one night on stage that turned in her favor. She added humor to her act and became a star, performing as part of the Minsky Brothers’ burlesque show in New York.

YouTube viewing

Well, I certainly didn’t expect a murder mystery from a movie titled Lady of Burlesque! Maybe I should’ve looked at the poster first. This one was kinda hard to follow for three reasons: a huge cast, with most of them talking a mile a minute, and in a hipster lingo from almost a century ago. It was worth it, though, to see Barbara Stanwyck shaking her moneymaker!

The history of burlesque dancing is a long one, covering much of world history, cultural mores, fashion, etc. Here’s a Cliff Notes version written by modern burlesque dancer Dita von Teese. For this post, we need to focus on one dancer in particular.

Gypsy Rose Lee was exposed to showbiz early in life. To support the family, she performed in vaudeville, dancing with her older sister, June Havoc, as kids. When June eloped, GRL was able to continue solo as a striptease artist. The legend has it that she chose this path when she had a wardrobe malfunction one night on stage that turned in her favor. She added humor to her act and became a star, performing as part of the Minsky Brothers’ burlesque show in New York.

Wednesday, April 8, 2020

Rain

Rain

YouTube viewing

W. Somerset Maugham was a doctor when his first novel, Liza of Lambeth, was published in 1897. It sold so well that he was able to pursue writing full-time. During World War One, he was one of a number of writers who doubled as ambulance drivers for the Allies, including Hemingway, EE Cummings, John Dos Passos, Robert Service and Gertrude Stein.

WSM would become one of the twentieth century’s most popular authors, with hits including Of Human Bondage and The Razor’s Edge. In addition, he was a secret agent during WW1 for a time; his later novel, Ashenden, is said to have been an influence on Ian Fleming when he created James Bond.

In 1921, The Smart Set, an American lit mag, published a short story by WSM called “Miss Thompson,” later known as “Rain.” It was inspired by a trip WSM took by steamer to Pago Pago, in American Samoa, a locale notorious as one of the wettest places on Earth. According to Wikipedia, it gets 119 inches of rain per year, with a rainy season lasting from November to April. During his trip, WSM encountered a Miss Thompson on the boat as well as a missionary man, both of whom were models for the story’s main characters. The guest house where WSM stayed is now a notable landmark.

YouTube viewing

W. Somerset Maugham was a doctor when his first novel, Liza of Lambeth, was published in 1897. It sold so well that he was able to pursue writing full-time. During World War One, he was one of a number of writers who doubled as ambulance drivers for the Allies, including Hemingway, EE Cummings, John Dos Passos, Robert Service and Gertrude Stein.

WSM would become one of the twentieth century’s most popular authors, with hits including Of Human Bondage and The Razor’s Edge. In addition, he was a secret agent during WW1 for a time; his later novel, Ashenden, is said to have been an influence on Ian Fleming when he created James Bond.

In 1921, The Smart Set, an American lit mag, published a short story by WSM called “Miss Thompson,” later known as “Rain.” It was inspired by a trip WSM took by steamer to Pago Pago, in American Samoa, a locale notorious as one of the wettest places on Earth. According to Wikipedia, it gets 119 inches of rain per year, with a rainy season lasting from November to April. During his trip, WSM encountered a Miss Thompson on the boat as well as a missionary man, both of whom were models for the story’s main characters. The guest house where WSM stayed is now a notable landmark.

Tuesday, April 7, 2020

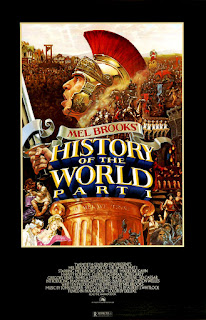

History of the World part I

History of the World part I

YouTube viewing

Oy gevalt, could we use some comedy right now! For a long time, I had avoided Mel Brooks’ History of the World part I because I had read it wasn’t as good as Blazing Saddles or Young Frankenstein, and as it turns out, I was right.

History was more cartoonish, but it lacked Saddles’ subversive bite or YF’s knowing winks to film history—it made me think of other films, like Life of Brian and Spartacus, but it made me wish I was watching those films instead. If this had been made by anybody else, it might’ve been passable, but Brooks sets a much higher standard for laughs than most.

History is exactly what it says on the tin; a series of vignettes set in different time periods throughout world history: the Stone Age, Biblical times, Ancient Rome, the Dark Ages and the French Revolution. Brooks appears as a variety of characters, along with his regular repertoire of actors—Harvey Korman, Madeline Kahn, Cloris Leachman, etc.—plus Gregory Hines, Dom DeLuise, Bea Arthur, and Brooks’ old boss from television, Sid Caesar. Orson Welles narrates!

YouTube viewing

Oy gevalt, could we use some comedy right now! For a long time, I had avoided Mel Brooks’ History of the World part I because I had read it wasn’t as good as Blazing Saddles or Young Frankenstein, and as it turns out, I was right.

History was more cartoonish, but it lacked Saddles’ subversive bite or YF’s knowing winks to film history—it made me think of other films, like Life of Brian and Spartacus, but it made me wish I was watching those films instead. If this had been made by anybody else, it might’ve been passable, but Brooks sets a much higher standard for laughs than most.

History is exactly what it says on the tin; a series of vignettes set in different time periods throughout world history: the Stone Age, Biblical times, Ancient Rome, the Dark Ages and the French Revolution. Brooks appears as a variety of characters, along with his regular repertoire of actors—Harvey Korman, Madeline Kahn, Cloris Leachman, etc.—plus Gregory Hines, Dom DeLuise, Bea Arthur, and Brooks’ old boss from television, Sid Caesar. Orson Welles narrates!

Friday, April 3, 2020

Baseball

seen online @ PBS.com

These past few weeks have been a trial for me, as I imagine they have been for you and everyone else, and the light at the end of the tunnel is still far off in the distance. This blog didn’t feel all that important for awhile... but seeing other people adjust to the current change in the status quo, and using technology to do it (this has been a pleasant discovery, for example), has been comforting, and I feel ready to get back on the horse with WSW, at least for now. Here’s hoping you and yours are safe and well during this tumultuous period.

Among the many things we’ll have to do without for awhile include sports in general, and baseball in particular. Major league ballparks across North America are currently silent when they should be loud and raucous right now—and because of that, documentarian Ken Burns recently petitioned PBS to rebroadcast on their website his original nine-part (now ten-part) miniseries Baseball. I watched the whole thing when PBS first broadcast it back in 1994, and seeing it again brought back pleasant memories.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)