YouTube viewing

Powell & Pressburger. I’ve wanted to see a Powell & Pressburger film for the longest time. I think I might’ve seen The Red Shoes during my video store years, but if I did, it might have been playing while I was helping customers and therefore couldn’t give it the attention such a movie deserves.

You can spot a P&P film for several reasons, but mostly because of the color. Did any other filmmakers in the Golden Age era use color as brilliantly as P&P? (Douglas Sirk probably comes closest.) Someone will correct me if I’m wrong, I’m sure, but I suspect whenever Hollywood used Technicolor back then, it was in a more show-off manner: as part of an “event” picture, like Oz or Wind or Robin, or for a splashy musical or a Cinescope picture.

I don’t get that sense from P&P. They used it prominently and they were obviously proud of it, but I suspect it was treated as just one of several integral elements to their movies which they happened to do better than most: the cinematography, the lighting, the set design—and I can sense this just from looking at clips of their films... though I could be wrong.

Michael Powell, from Kent, England, started out as a gofer in a French studio in the 20s—even did a little acting. Worked for Hitchcock at one point. By the 30s he had moved up to screenwriting and in 1931 he directed his first film, Two Crowded Hours. He had a strong directing career in the UK throughout the 30s. Emeric Pressburger, a native of what was then Austria-Hungary, was a journalist before becoming a screenwriter in Germany. When the Nazis came to power, he moved to Paris and then England in 1935, where he worked with fellow Hungarian filmmaker and emigre Alexander Korda.

In 1939, Korda started production on a WW1 movie, The Spy in Black, based on a novel, as part of the British studio he founded, Dunham Film Studios. Powell directed and Pressburger wrote the adaptation. It was their first collaboration and it performed well. They teamed up again for two WW2 movies: Contraband a year later and 49th Parallel the following year, a film which won Pressburger a writing Oscar. In 1942 the duo shared writing, producing and directing credits on One of Our Aircraft is Missing. This time they both shared an Oscar nomination for their screenplay.

With Aircraft, they established the name of their production company, The Archers, with a specific vision for producing films that ensured they’d share responsibility for their work. The buck stopped with them and they answered only to their financial backers. The results speak for themselves: The Red Shoes, Black Narcissus, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, Tales of Hoffman, etc. They were the cream of the crop in British cinema.

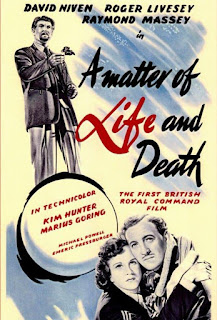

Matter is a good example of this. David Niven is a British fighter pilot during WW2. His plane is about to crash but American WAC Kim Hunter makes contact with him via radio before he goes down. Niven falls in love with the sound of her voice. Miraculously, he jumps out of his downed plane and survives, but he should have died in that moment, and because of this second chance Niven and Hunter meet and mutually fall in love. The afterlife bureau in charge of such things tries to reclaim Niven. Officially it’s not a remake of Here Comes Mr. Jordan but obviously it’s a very similar plot.

What was it with all those afterlife movies in the 40s? This movie, Jordan, Cabin in the Sky, Heaven Can Wait—seemed like a lot of people had it on their minds back then. Maybe the war brought out feelings of mortality in filmmakers?

Matter was not what I expected. It’s more than a supernatural love story; while not quite an all-the-way war movie, P&P’s screenplay has a few things to say about war in general and seems to indict its own country for its long history of imperialism. The fact that Niven’s character is a British serviceman plays a factor; in the afterlife trial to determine Niven’s fate, England’s record of conquest and colonialism is called into question by the prosecution, represented by a colonial-era American. The impression I got was that the defense’s argument was that Britain, over and above other countries, was culpable for the wars they started and/or perpetuated throughout history and Niven, as a British combatant, should not be let off the hook if his number was up.

I’m not sure if that argument holds water; it’s not like Niven started WW2. If he had done something in combat that was so egregious it was felt he needed to pay with his life, I could buy that; that way when he falls in love with Hunter, who only knows him through a limited context, he could say he was a changed man and deserved a second chance, to redeem himself, which fits the defense’s “Love Conquers All” argument.

Despite this probably-flawed interpretation—and while I don’t want this to be yet another bashing of the overrated Jordan—this does strike me as a more sophisticated and thought-provoking screenplay. I’d need to see this again for sure.

I liked the acting. Roger Livesay plays a doctor who suspects Niven’s assertions about surviving his plane jump, and his subsequent contact with the afterlife, is all in his head. He was also in Blimp and I Know Where I’m Going! Raymond Massey played the American colonial who prosecutes Niven; I didn’t recognize him at first until I associated his name with his face and I remembered him from his creepy-yet-comic turn in Arsenic and Old Lace. I liked him a lot; he was very convincing. He was also in 49th Parallel.

Matter’s cameraman was Jack Cardiff, a pioneer in Technicolor filming. He was second unit cameraman on Blimp and P&P liked him so much they kept working with him, as cinematographer. He’s pretty much a legend. P&P are known for their use of color, but in this movie, the afterlife scenes are in black and white.

Matter was the first Royal Command Film Performance. What’s that? It’s a charity screening in which the Royal Family gets to attend. Matter’s royal screening was held November 1, 1946 at London’s Empire Theatre. Last year’s performance was for 1917.

P&P broke up in 1957. Powell continued as a solo artist, making movies like Peeping Tom, which hurt his career for years due to its controversial nature. Pressburger became a published novelist. The two reunited for two more movies in the late-60’s and 70s, and that was it, but their legacy as renowned filmmakers lives on.

This is my favorite P&B movie. I think it's a genius idea to have Earth, even during war, in color and the afterlife in black and white. I couldn't recognize Massey at first, too. Marius Goring as the guy who needs to fix the mistake is another highlight.

ReplyDeleteI hope now the problem with my comments is solved. Cheers!

Looks like it’s fixed on my end.

ReplyDeleteSomeday I’m gonna sit down with more of their films. Visually I’ve always found them enchanting even if I couldn’t tell what they were about based on clips and stills.